Published February 2, 2024

Symmetry is all around us. We as human beings are symmetrical. Our lungs, kidneys, and brains are all perfect examples. If you were to slice each of these organs in half, you would have a mirror image of the other. As a society we also think symmetrically – good and evil, progress and reaction. In nature, symmetry can be found in petals, leaves and wildlife like starfish, crabs and octopi.

As deeply as symmetry is ingrained in our everyday lives, it can also be found in music. Downbeats and upbeats, crescendos and decrescendos, the list goes on and on. The classical period was all about symmetry and balance, composers Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven used these principles consistently in their music.

Prolific composer and conductor, Leonard Bernstein, touches on this before analyzing the symmetry and balance found in Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 in his Norton Lecture series. These principles were not exclusive to No.40, but the opening of the first movement provides a great example as to how Mozart explored them.

Before we launch into the video, here are a few terms you might find useful to understand when listening to Bernstein:

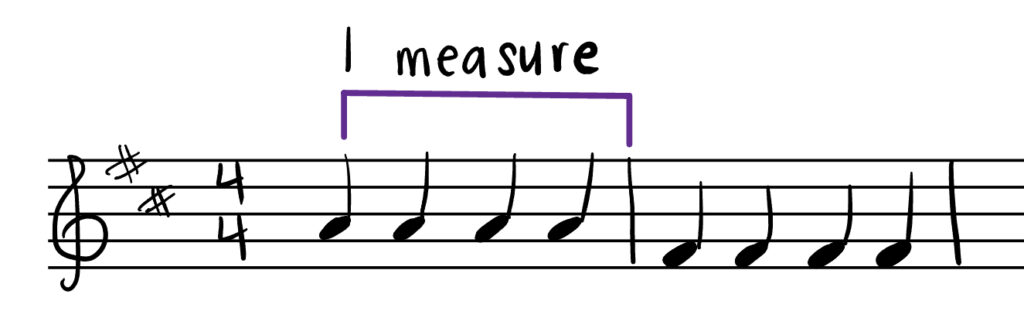

Bar or measure: single unit of time defined by a specific number of beats within a piece of music

Phrase: a passage of notes that work together to create a musical thought that sounds complete when heard on its own.

Main theme: the main melody or idea that you hear, usually happens at the beginning of a piece to establish melodic material for the rest.

Vamp: a repeating musical figure, accompaniment or idea, usually short.

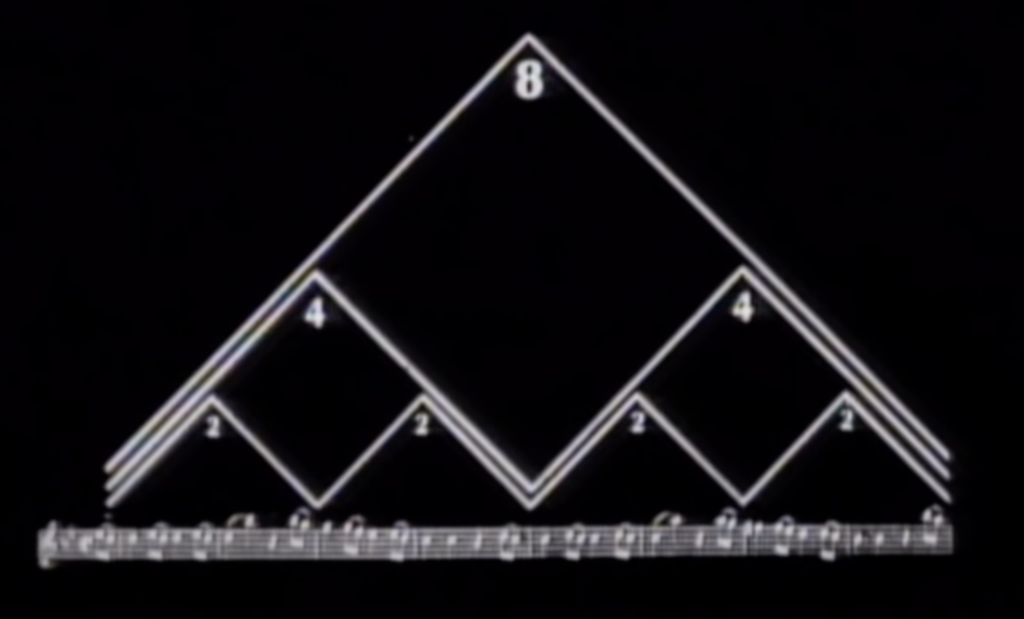

The symphony begins with a symmetrical main theme and idea, starting with a short 2 bar phrase that is immediately countered and answered by a complimentary 2 bar phrase, creating a symmetrical 4 bar structure. As listeners we can hear that it is clearly incomplete, which then leads us to another 4 bar phrase that can be broken up into another two symmetrical 2 bar phrases.

Bernstein says, “The theme is balanced, four symmetrical strings of two bar phrases perfectly balanced and comprising in themselves, a string of dualities; two within four, within eight.”

He goes on to explain, “If we stick to that symmetrical principal then the introductory vamp accompaniment preceding the theme should also be 8 bars [or 4 or 2]… always in absolute symmetry posed by the theme itself.”

Bernstein extrapolates the form and main theme of Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 and creates a 36-measure piece using that tactic of absolute symmetry. He leaves us with a drawn-out melodic idea using mind-numbing repeats to show us that if Mozart were to stick with the symmetrical form as expected, the music would be boring.

The lecture ends with these words that highlight Mozart’s mastery of composition.

“Symmetry is not necessarily balance that’s a precept we learned long ago that is worth saying again, and what Mozart has done as any great master does, is to make the leap from prose-y symmetry into poetic balance, that is into art.”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 in G minor, K. 550 was written in 1788. This four-movement symphony exists in two versions, the second including material for a pair of clarinets with the other wind parts altered to accommodate this addition.

In the summer of 1788, Mozart was particularly busy as he composed his 39th, 40th, and 41st symphonies consecutively. According to Andrew Clements and Tom Service, authors for the Guardian, conductor Niklaus Harnoncourt insists that Mozart intended the three symphonies were meant to be a unit. Clements says, “Harnoncourt’s reasoning goes, would explain the thematic connections between the three works, and also why the opening to the E-flat Symphony K543 is conceived like an overture, and why neither that work nor the G minor Symphony K550 has what he calls a ‘proper’ finale, unlike the C major Jupiter Symphony K551, whose last movement seems intended to sum up everything that has come before.”

In considering Bernstein’s praise of Mozart’s leap into poetic balance, we find another (somewhat weak but still existing) case for support of Harnoncourt’s theory on the three symphonies being composed as a unit.

“When you consider that Mozart was obsessed with Baroque music around 1788 (he wrote the symphonies just before he made arrangements of Handel’s Acis and Galatea and Messiah), and that there was no known reason for him to compose these pieces, the idea of some grander conception is at least a possibility,” says Service. “Harnoncourt’s idea could simply be a typically wacky extrapolation, but it’s an excuse to go back to these pieces and hunt again for deeper connections between them.”

Did Mozart intend for these principles of symmetry and balance to make Symphony No. 40 into one huge development to then connect all three symphonies with Symphony No. 39 as an introduction and Symphony No. 41, Jupiter, as the proper finale? Or was he just an inspired composer eager to continue exploring and creating masterpieces in the summer of 1788?

Mozart, Strauss & Evangelista – Matinee

February 10, 2024 at 3PM

Caleb Young, Conductor

Jessie Brooks, Horn

CONCERT PROGRAM:

- José Evangelista, Airs d’Espagne pour orchestre à cordes

- Strauss, Horn Concerto No. 1

- Mozart, Symphony No. 40